IMAGINE you are on your smart ‘phone (assuming you have one) and someone comes up to you and asks whether you believe in electricity. You might be forgiven for looking askance at this person and assuming that they were mad. But think about this for a moment – 500 years ago Europeans would have been equally nonplussed had they been asked whether they believed in God. It is this sort of insight that marks out A Wonderful LIFE by philosopher and psychology researcher Frank Martela.

God’s presence was everywhere in the life of our ancestors. “Theirs was a world dominated by the supernatural – spirits, demons and magic,” writes Martela. “The existence of God and spirits wasn’t a question of belief but an immediate certainty.” Just like electricity is today. However, if you ask many people about God now it is unlikely to elicit quite the same degree of certainty. It is often thought that people began to seriously question the meaning of life after the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. But the findings of geologists had been undermining the veracity of the Bible for years and as early as 1834 the essayist, satirist and historian Thomas Carlyle is thought to be the first person in the English speaking world to coin the term ‘meaning of life’ in his extraordinary book Sartor Resartus (meaning tailor re-tailored). Indeed, Carlyle makes his protagonist Herr Teufelsdrockh question everything. “Doubt had darkened into Unbelief,” says he; “shade after shade goes grimly over your soul till you have the fixed, starless, Tartarean black.” Today, we might call this an existential crisis and in fact Soren Kierkegaard, often thought of as a forerunner of existentialism, was also active that this time.

For Martela the ‘combination of losing touch with religion through the rise of the scientific world view plus the Romantic notion that, to truly live, you must experience your life as highly meaningful, formed a perfect storm that gave rise to the concept of the existential crisis and conditions endemic to our modern culture today, a society where the lack of meaningfulness can become all-consuming’. The rise of the cult of the individual also contributed to the search for meaning. The sense of the autonomous individual, however, is a relatively recent phenomenon. Indeed, as Martela notes, ‘the whole idea of a private inner self beyond one’s public self started to appear in the literature only from the 16th century onwards’.

According to Martela, what we actually need to do to make sense of all this is to shift from the ‘meaning of life’ which is ‘about something beyond life in question justifying its meaningfulness’ to ‘meaning in life’. And once you make that move then you find that you already have ‘many relationships, experiences, and emotions in your life that already feel meaningful to you regardless of a rational explanation as to why’. And it’s not Sartre that expresses this but Simone de Beauvoir who emphasises that we’re ‘already situated’. In an introduction to Beauvoir’s Introduction to an Ethics of Ambiguity it is claimed that she ’emphasises the inter-subjective dimensions of existence’ and argues that ‘I cannot will my own freedom without, at the same time, willing the freedom of others’, echoing Kant’s categorical imperative.

From all this Martela identifies ‘autonomy, competence, relatedness, and benevolence’ as the key factors in what makes for a meaningful life. These are Ok as far as they go. However, it could be argued , as Daniel Dennett does in From Bacteria to Bach and Back that many animals display competence but it’s the injection of comprehension that introduces consciousness, which is a central feature of humanity if not exclusive to it. Again ‘relatedness’ is a thin word for what might better be described as our social being. Indeed, for the sadly recently deceased Rutger Bregman in Human Kind – A Hopeful History our social being was our super-power over the more individualistic Neanderthals whose superior intelligence could not spread knowledge as widely and as quickly as it could by the more social Homo Sapiens. It is something that Martela does at least recognise in passing when he writes that ‘we need to work together to strengthen the forms of community available to us’. The word ‘benevolence’ is too vague a concept which might better described as altruism which some evolutionary biologists – including Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene – argue that altruism forms part of our genetic make-up, even if it competes with our more ego-centric traits.

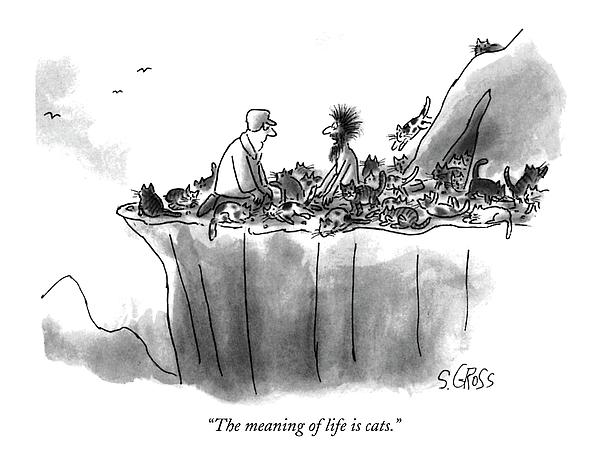

In Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy a super computer designed to find the answer to the meaning of life eventually replies ‘forty-two’. As Martela says the answer points to the ridiculousness of the question itself.

Clearly there are still many people who do draw meaning from a higher authority but for those that don’t then, equally clearly, finding meaning in life – rather than of life – is a more fruitful quest. But there is a danger that starting from the perspective of the individual and working from there to inter-subjectivity is starting from the wrong end. Contrary to our current obsession with the individual – exemplified by the metaphysical Homo Economicus – it could be argued that our meaning starts with our social being and the problem then becomes how we create the conditions in which the full potential of the autonomous citizen can be realised as it emerges from the collective – without abandoning the latter.

So what are we saying? That life, by which we mean our individual life, has no meaning in the abstract? – Because anything can only MEAN something TO somebody (some mind capable of registering a Meaning). One’s existence means something to others, then. If I don’t mean anything to anybody, I become so isolated I might as well not live.

Is that reasonable, or have I got it wrong? Christopher.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Christopher, thanks for your comment to which I have replied and you can read here .

Best wishes, Dickie.

LikeLike

Hi Christopher, I’m not sure what it would mean to say meaning is abstract. I think that one of the main principles to take away from this is that if meaning can make sense in this life then it is meaning that is embedded in and emerging out of our grounded social being rather than from an external source like a supernatural being. It is in the very relatedness with other people that meaning takes shape as embedded autonomous individuals but we need to create the conditions in which as many people as possible can achieve that state. The conditions generated by neoliberalism, then, are the antithesis of the required conditions because it denies any relationship with others that is not transactional. That is why, I think, neoliberalism leads to utter isolation and needs to be replaced with a more communitarian society in which secular meaning with others can flourish. Hope that makes sense and eased your concern that you don’t mean anything to others! I think that the very opposite is true.

LikeLike