IS there some feature, or set of features, that set humans apart from all other animals? And if there is, does that make us different in kind or degree? Until relatively recently it was thought that humans were unique. It is an idea promoted throughout the millennia by various religions but also by secular thinkers – like Aristotle’s claim that that we are uniquely political animals.

One recent attempt to furnish us with unique characteristics is ventured by Jeremy Lent in The Patterning Instinct. For him, as the title suggests, it is our capacity to seek out patterns that sets us apart from other animals. According to Lent all organisms create a ‘niche construction’, which is shaped by their environment and which they shape in turn. And the place that humans have created for themselves is a ‘cognitive niche’, which is a ‘result of using their unique cognitive powers to learn to co-operate with others and collectively discover new ways to manipulate their environment’. For Lent every human society ‘shapes the cognitive structure of the individuals growing up in in its culture through imprinting its own pattern of meaning on each infant’s developing mind’. And language is the most important vehicle for societies to mould a developing child’s mind.

Crucially for his argument, he claims that there are two ‘tightly interconnected, coexisting complex systems’ – which he calls the ‘tangible’ and the ‘cognitive’. Tangible refers to everything that can be touched, the ‘physical infrastructure’. Cognitive refers to what cannot be ‘touched but exists in the cognitive network of a society’s culture: its language, myths, core metaphors, know how, hierarchy of values and world view’. And according to neuroscientists the cognitive facility emerges out of the prefrontal cortex (PFC), which ‘mediates our ability to plan, conceptualize, symbolize, make rules, and impose meaning on things’. While advanced PFC functions exist in other non-human animals, their ‘predominance in humans is overwhelmingly different in magnitude and scope, accounting largely for our current domination of the world’. So, Lent’s position is not that we are different in kind but in degree, even if the difference is vast.

This a long book and Lent goes on to trace the rise of agriculture and the resulting increase in anxiety and hierarchies and early civilizations. But he is particularly interesting when he writes about how patterns diverged between the West and the rise of dualism in ancient Greece with its consequent split Cosmos and split humans; and the ‘harmonic web of life’ associated with Eastern philosophies like Taoism in China. In ancient Greece ultimate reality was transcendent. “In the Chinese Cosmos there was no eternal soul; no pure, abstract mind creating and directing the universe,” writes Lent and further: “Instead, the Chinese found the most profound source of meaning within the everyday, material dimension of life.”

Lent’s big claim is that the dualism in the West led to a mindset that split humanity from nature and to a ‘command the world metaphor’. Leading this change was Francis Bacon who, in the early 17th century, wrote about the scientific method in terms of putting nature into constraint and of hounding her ‘in her wanderings’. It was an influential position that helped create the metaphor of ‘conquering nature’. It was a world view given support by the sense of God as divine lawgiver, who gave humanity dominion over nature – a concept entirely alien to the Chinese culture of the time. But a further complication came when scholars of the Middle Ages like John Scotus, Augustus and Aquinas concluded that reason could be used to examine faith – indeed, Aquinas placed the intellect as the seat of the soul. This contrasted with the other great seat of civilization – the Arab world, where reason remained in the service of faith. And it was, claims Lent, the Western rise of theological reason that, combined with the reason of science, set the West on the road to scientific, political and military dominance of the West.

It is a mindset that continues to feed into our fixation with unending economic growth and the over-reach of consumption that threatens the future of humanity and all the flora and fauna that we will take with us – although not the planet itself, which continue long after we are gone.

Ultimately, Lent calls for a Great Transformation in which the old metaphors of domination are replaced by ones that recognise the ‘intrinsic interconnectedness between all forms of life on earth and seeing humanity as embedded within the natural world’. From where we are it seems unlikely that humanity will be able to achieve this transformation. Our fatally flawed system of representative government has been bought and tamed by huge multi-national companies and uber-rich individuals, our governors are still enthralled by GDP growth and consumption – and there appears to be no sign that this is going to change soon.

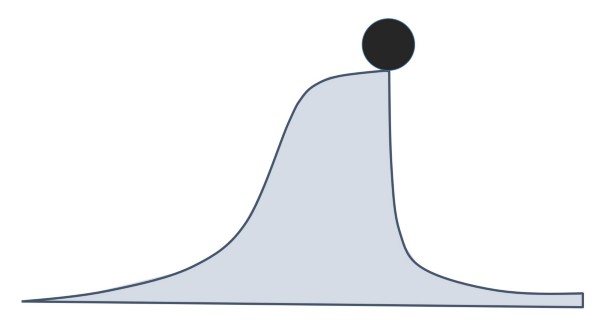

Lent is more optimistic and he deploys the internet to give him hope in that he believes that throughout history new ways of thinking have gained momentum until a tipping point when the ‘stickiness’ that kept people attached to their old pattern of thinking is superseded by the pull of new ideas. He adds: “In the age of the internet, this tipping point can conceivably be reached much more quickly than in the past.”

Is this just wishful thinking? Well, what Lent does not mention is that vast swathes of the internet are also owned by huge corporations. And it is difficult to dig oneself out of a pessimistic frame of mind. From our perspective it is hard to see how the transformation that Lent calls for will happen. All one can do is to continue to resist the current ‘cognitive niche’ – or one might say ‘rut’ – and hope he is right.

I have left comments on your series of blogs on a number of occasions in the past. As I heard nothing further, I had to wonder whether my efforts were unwelcome or perhaps never reached anyone. It would be good to know the answer to that: I mean, if my comments are disqualified by my my not being a trained philosopher, I’ll keep silent.

On the present question, it seems to me that Lent is looking in the wrong place for the difference between humans and other animals. And therefore the dependant specu- lations fall into a sort of philosophical swamp. I think the key factor is that human’s can think in terms of Cognitive Intent. I am trying to make a distinction between this and Instinctive Intent (which may be checked out as to how evolutionary its origin is). the presenT!) This capacity is clearly linked to awareness of Time, which animals also do not have, or not in the same degree. Which is important because Intent looks to the Future. Now surely the Future is not a real place. The real place is not only Here but Now. And the Future is a place of imagination (until it becomes the Present!). So if animals have Intent at all, it will be Instinctive; but not Cognitive – in the way that Humans are capable of because of their awareness of Time and their capacity to use their Imagination in thinking of the Future. Towards which, in this way, they are capable of Cognitive Intent.

It would be most interesting to hear whether you find any of my suggestions useful.

Christopher Browne.

May I draw to your attention that my email address has been changed since last time I wrote to you online? it is now: christopherbr75@gmail.com.

LikeLike