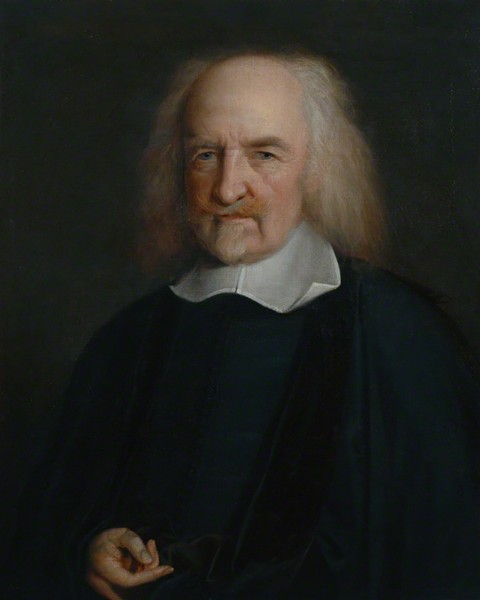

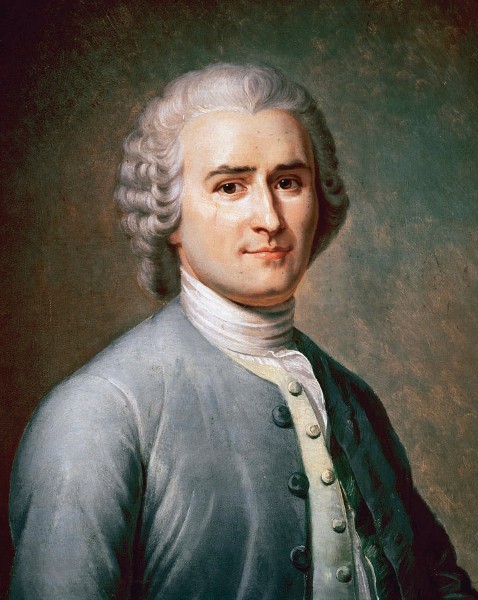

ARE human beings – and human life itself – fundamentally good or bad? It is a question that has taxed philosophers for millennia. In one of its most recent manifestations it is represented on the one hand by Thomas Hobbes who regarded life before civilisation as being ‘nasty, brutish and short’, which we could only escape by surrendering our freedom to a supreme leader – a leviathan, which happens to give its name to his magnum opus. On the other hand we have Jean Jacques Rousseau who argued the complete opposite – that the innocence of humanity was corrupted by civilization.

But what if the very idea of whether humans are good or bad is a category error? That is the claim made by the late David Graeber and David Wengrow in The Dawn of Everything – A New History of Humanity. They point out that the terms ‘good’ and ‘bad’ are purely human concepts. No one would claim that a non-human animal or a plant was good of bad. “It follows that arguing about whether humans are good or evil makes as much sense as arguing about whether humans are fundamentally fat or thin,” they write. In fact, their research shows that human society before the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions was neither brutish not idyllic. They claim, on the contrary, that the ‘world of hunter gatherers as it existed before the coming of agriculture was one of bold social experiment, resembling a carnival parade of political forms’. Further: “And far from setting class difference in stone, a surprising number of the world’s earliest cities were organized on robustly egalitarian lines, with no need for authoritarian rulers, ambitious warriors – politicians, or even bossy administrators.”

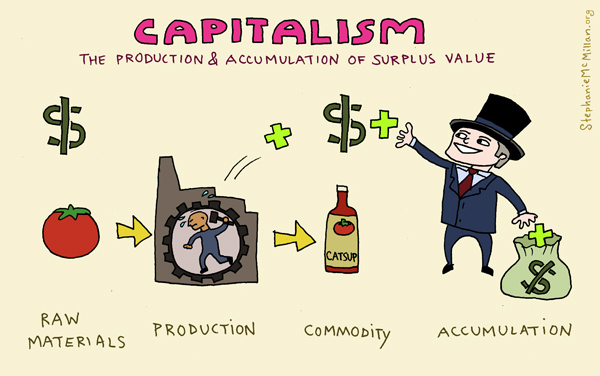

From their research, the authors have found that neither Hobbes nor Rousseau were right. There was no single pattern. “The only consistent phenomenon is the very fact of alteration, and the consequent awareness of different social possibilities,” they write. So, when we ask what the origins of social inequality were, we are asking the wrong question. “If human beings, through most of our history, have moved back and forth between different social arrangements, assembling and disassembling hierarchies on a regular basis, may be the real question should be ‘how did we get stuck?’ How did we end up in a single mode?” That mode, they argue is eminence and subservience – once seen as temporary expedients or even grand theatre – now embedded as ‘inescapable elements of the human condition’.

The key for David Graeber and David Wengrow is not that inequality has its roots in pre-civilization society and is now an inevitably permanent feature of human society. It is not that we have lost a kind of innocence as in the Christian myth of Original Sin. What we have lost is the ability to even envisage different social and economic orders. They write: “The contrast with our present situation could not be more stark. Nowadays, most of us find it increasingly difficult to even to picture what an alternative economic or social order might be like. Our distant ancestors seem, by contrast, to have moved regularly back and forth between them.”

If we are to break the mould of class division and economic inequality the, the authors say, we must rediscover three freedoms – and not just the negative freedom like freedom of speech. They are: 1 – the freedom to move or relocate from one’s surroundings; 2 – the freedom to shape entirely new social realities, or shift back and forth between different ones; 3 – the freedom to ignore or disobey commands issued by others. Another overarching freedom which enables these three is the positive freedom which empowers people to act and not to be merely passive recipients. So, for example, while we have the negative freedom to relocate, the ability to actually do so depends on whether or not you have the required social and economic security. It means developing the idea of active citizenship – to be citizens rather than just ‘consumers’, ‘constituents’, taxpayers’ or ‘subjects’. (This will be the subject of a future blog).

Above all we need to recognise that civilization and complexity need not come at the price of human freedom, that participatory democracy – maybe in the form of citizens’ assemblies – is not necessarily possible only in small groups but impossible to scale up to city or national level. We need to rediscover our ability to imagine alternatives and to consign to the dustbin of history the toxic phrase ‘there is no alternative’.