IT is often argued, with some truth, that we live in an age of wilful ignorance in which thought is undervalued and we are encouraged to live in the now.

Delayed gratification is discouraged and replaced with the present. Commercial institutions have fuelled this process by encouraging us to think of ourselves as free-standing, self-interested individuals who want to buy things NOW, even if it means going into debt. In the political field it means the rise of populism in the USA, Brazil, the UK, Russia, Hungary, Turkey and India where it has gained power. And in many other countries it lurks beneath the surface.

But is there another cause for this phenomenon? Well, according to Brazilian philosopher Marcia Tiburi in The Psycho-cultural underpinning of Everyday Fascism – Dialogue as Resistance, yes there is. For her, central to the problem is an absence of shame among many leaders like Bolsonaro, Trump, Johnson, Erdogan, Modi and Putin. It’s this lack of shame which enables, indeed empowers them to lie with impunity. Tiburi writes: “The ridicule of several of the scenes involving these characters sounds to their followers like heroism. Therefore, this strange heroism of the tyrants of our time has become something ‘pop’ in a process of profound ‘political mutation’.”

In this world consumerism fills the vacuum, the emptiness of consumption. “We flee from analytical and cultural thinking through the consumerist emptiness of language and repetitive language. We flee from the discernment that analytical and critical thinking demand. We fall into the language of consumerism.” Now it should be said here that it would be wrong to suggest that there was a time when humans were perfectly rational but have somehow become vacuous idiots. It’s more that certain forces are becoming better at exploiting our inherent irrationality and undermining our counterbalancing ability to think – at least some of the time!

With that important caveat in mind then, Tiburi identifies the ‘great voids’ that have emerged in recent years. One is the ‘void of thought’ which Hannah Arendt identified as characteristic of Adolf Eichmann.

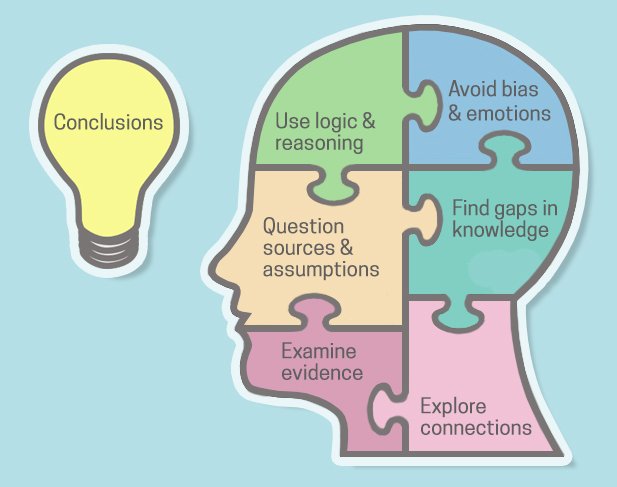

This emptiness of thought in Eichmann entailed the ‘absence of reflection, of criticism, of questioning and even discernment’. Tibury adds: “We can say that, in our time, this is becoming more and more common. More and more people are giving up the ability to think.” And in place of this ability comes ready made ideas or cut-and-paste ideas, as she puts it, largely distributed through social media networks.

Another great void, according to Tiburi, is an emptiness of feeling. She writes: “We live in a world that is increasingly anesthetized, in which people become incapable of feeling and increasingly insensitive.” It’s not that we don’t have emotions but, she argues, we ‘can speak of an emptiness of emotion precisely in the context in which people seek any kind of emotion.’ Further: “The inability to feel makes the field of sensitivity in us a place of despair. From joy to sadness, we want religion, sex, films, drugs, radical sports, and even food to provoke more feeling.”

Not all is lost, however, because for Tiburi at least part of the answer lies in the encouragement of dialogue, very much like the skill we practice in Salisbury Democracy Café. Tiburi argues that: “Dialogue is not just a form of philosophy, rather philosophy in its pure state. Dialogue is the attitude that can alter the spiritual and material condition in which fascism arises.” For Tiburi dialogue is a ‘type of psycho-social resistance, which holds the power of social transformation at its most structuring level – shaping dialogue matters when we want a democratic society’ and it is also the specific ‘form of philosophy as a practice, or as activism’. Furthermore: “We need an education for democracy that is education for art and poetry, for science and critical thinking.”

And she claims that dialogue at all ‘levels is undesirable in authoritarian systems’.

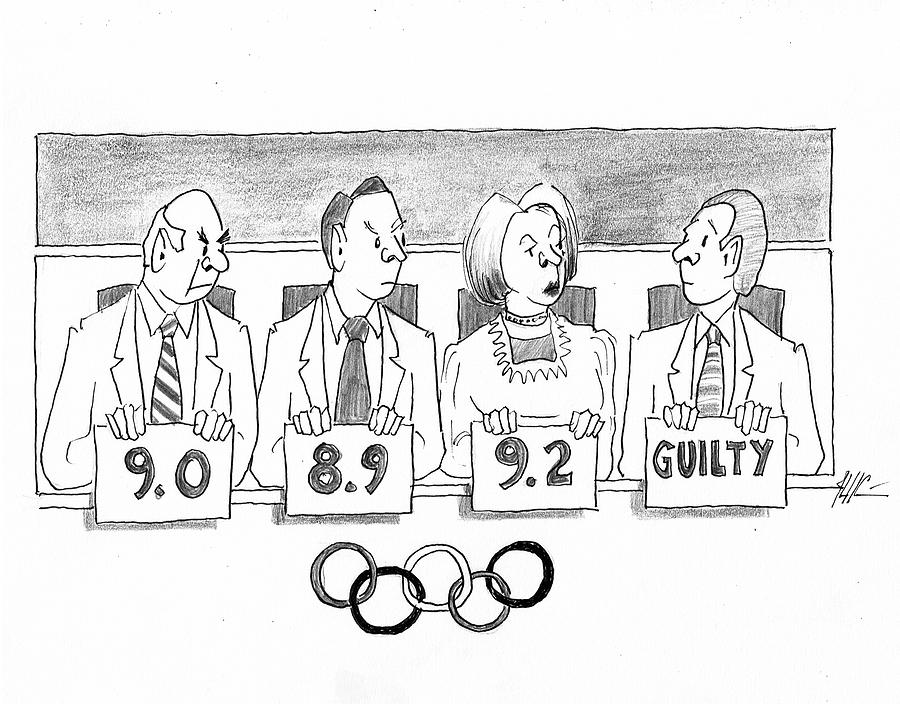

It’s hard not to equate Tiburi’s thoughts with those of deliberative democracy promoted by Salisbury Democracy Alliance (SDA) both in the democracy café and in its campaign for Citizens’ Juries. It’s the very point that SDA made in its highly successful stand in People in the Park last year – and will make again this year – when it argued that without the engagement of ordinary people in real dialogue in general, and Citizens’ Juries in particular, our representative form of government remains just that – representative and not fully democratic. And as, the Tory grandee Lord Hailsham once said, it is always in peril of slipping into an ‘elective dictatorship’.