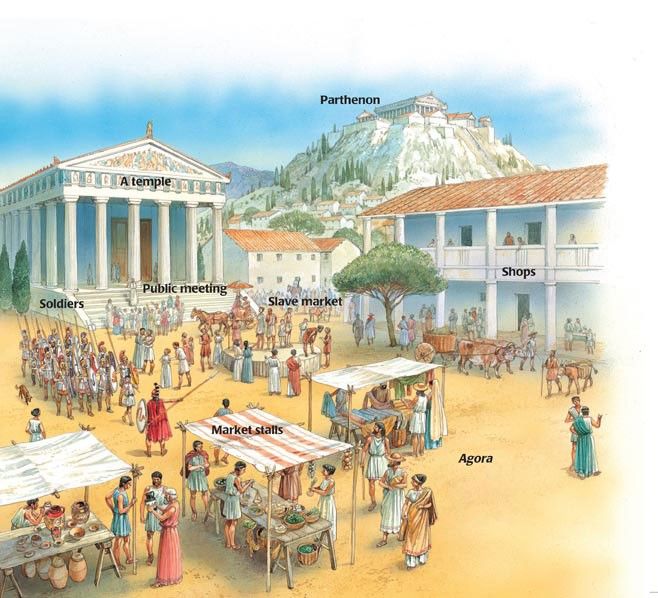

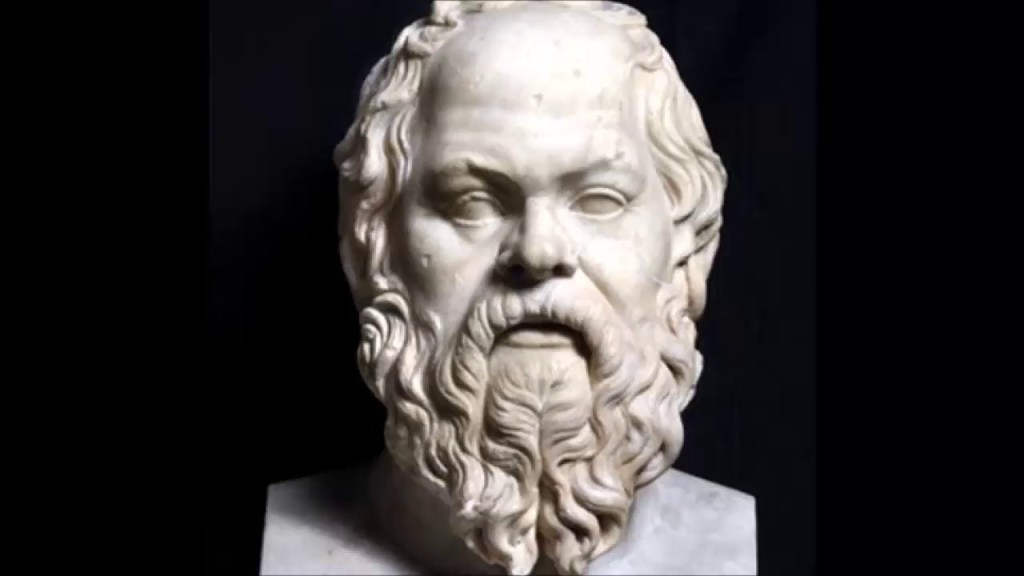

IN some parts of Western society individualism rules supreme and reaches its apogee in neoliberalism in which the only relation that exists between individuals is transactional. This relationship is encapsulated within the mythical figure of Homo Economicus who is supposedly driven solely by rational self-interest and becomes a consumer and spectator in society rather than a participant. Philosophically, it is expressed in its purest form as methodological individualism, which asserts that all attempts to explain social or individual phenomena are to be rejected unless they are couched wholly in terms of facts about individuals. The problem with this position, however, is that it excludes any individual for whom a sense of community is constitutive of how she perceives her being.

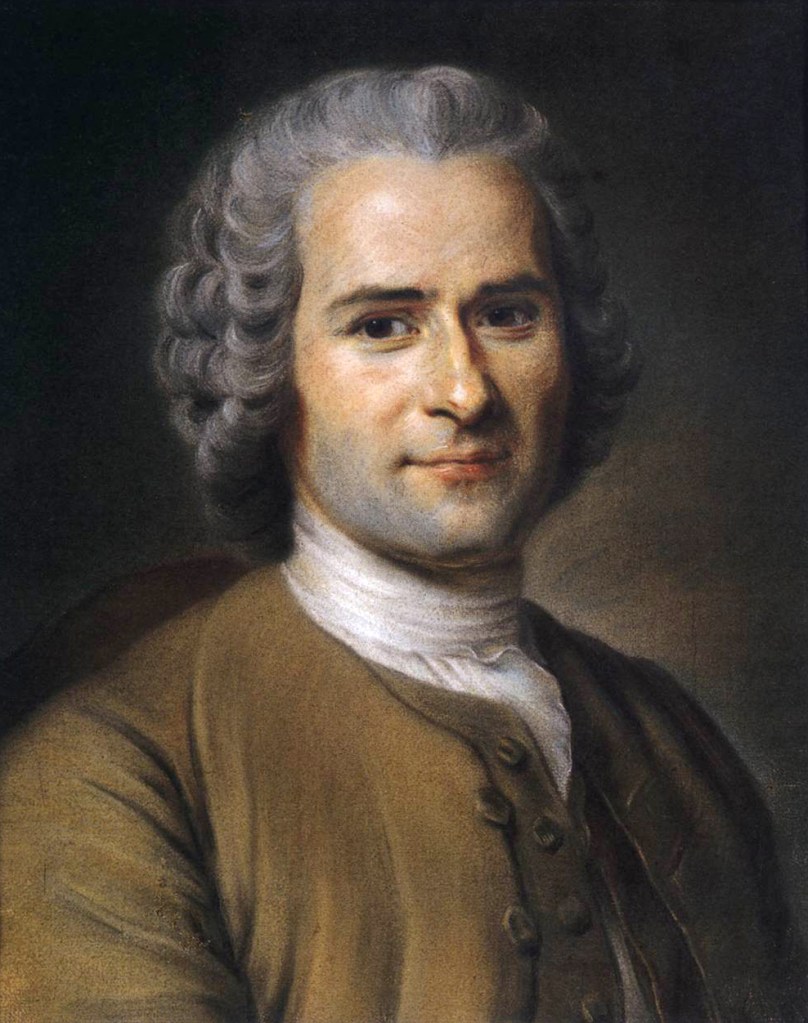

It should be said that other political philosophies are available and one such is provided by the economists Paul Collier and John Kay in their book Greed is Dead. They argue that that extreme individualism ‘is no longer intellectually tenable’, raising the question as whether it was ever intellectually tenable. It could be argued, of course, that when the luminaries of the Enlightenment suggested that we should use a bit more reason in our lives, they were also promoting the rights of the individual against the oppressive State. Perhaps this was necessary at the time – and the rise of universal human rights still rightly protects the individual in this sense – but perhaps now the dominance of the individual has gone too far and we need to address the imbalance because, as Collier and Kay point out ‘human nature has given us a unique capacity for mutuality’.

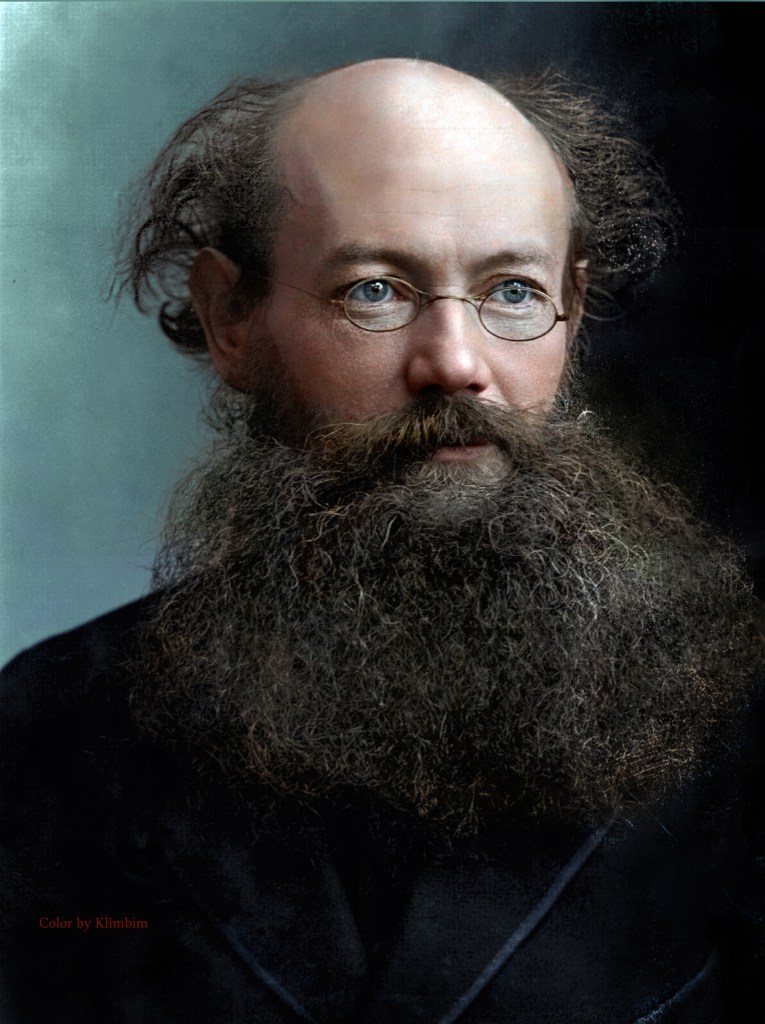

The importance of mutuality was also stressed by the Russian thinker and anarchist Kniaz Petr Alekseevich Kropotkin in his 1921 work Mutual Aid: A Function of Evolution in which he writes ‘besides the law of Mutual Struggle there is in Nature the law of Mutual Aid, which, for the success of the struggle of life, and especially for the progressive evolution of the species, is far more important than the law of mutual contest’. The us of the word ‘progressive’ here is significant because it sets Kropotkin up in a communitarian tradition that is very different from that of Collier and Kay, as we shall see.

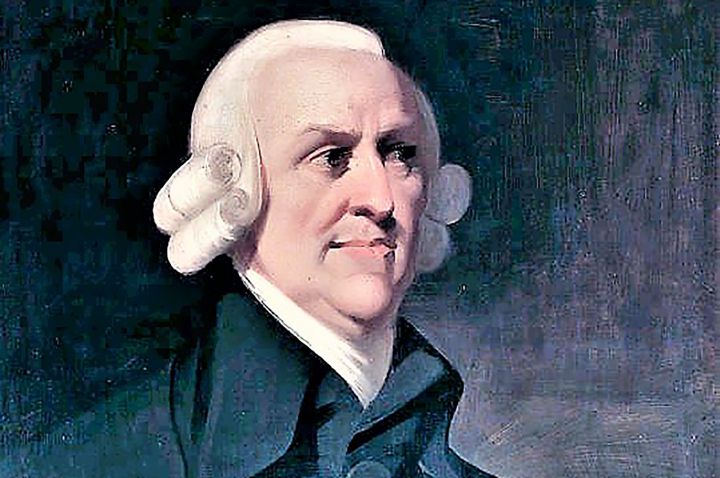

Nevertheless, the authors do agree with Kropotkin that biology ‘far from lending support to the premises of individualism, undermines them’, and they point to myriad organisations that are neither individualistic nor statist including families, clubs and associations as well as , one might add, political parties and trade unions. Adam Smith, primarily a moral philosopher but with his book The Wealth of Nations regarded as the founding father of modern economics, fully acknowledged the complexity of humans and their relationships – and yet he has been trivialised by neoliberals to mean the benefits of the invisible hand of self-interested individuals, a metaphor that he used just once in his otherwise rich and rewarding book.

Collier and Kay make their position clear when they write: “And we claim that agency – moral, social and economic – is not polarized between the individual and the state, but that society is made up of a rich, interacting web of group activities through which individuals find that fulfilment.” It’s probably fair to say that the authors fit firmly in what might be called the conservative tradition of communitarianism alongside Edmund Burke’s ‘little platoons’ and Hegel’s ‘civic community’, although they would probably balk at his valorisation of the State. Indeed, their central argument is that there has been too much centralization in the State. Even our much-loved NHS comes in for severe criticism and they argue that health care is ‘well suited to decentralized provision’, although they don’t say how this would happen without health care descending into a postcode lottery .

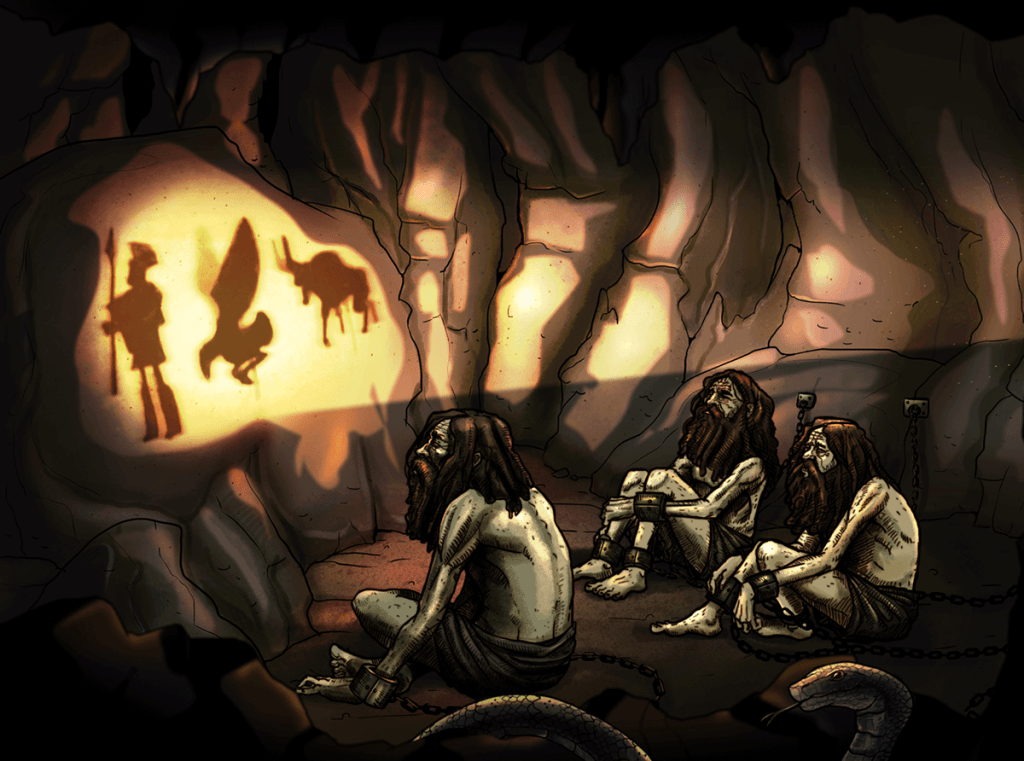

As we have seen, this is very far from the communitarianism of Kropotkin or, indeed, his fellow anarchist Noam Chomsky who wrote in his book On Anarchism that while he looks forward to a post-capitalist society and the ‘dismantling of state powers’ he also acknowledges that ‘certain aspects of the state system, like the one that makes sure children eat, have to be defended – in fact defended very vigorously’. And Karl Marx explored the notion of communitarianism, which he rooted in our material being in that the ‘sum total of these relationships of production constitutes the economic structure of society – the real foundations on which rises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness’. Famously in A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy he wrote: “It is not the consciousness of men that determine their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.”

Lest we forget, and in response to the individualism of Martin Buber in a previous blog, religion can also deliver a more communitarian approach. In his book The Way of St Benedict the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams writes: “Or, to pick up our earlier language, it is the unavoidable nearness of others that becomes an extension of ourselves. One of the things we have to grow into unselfconsciousness about is the steady environment of others.”

One of the most appealing aspects of communitarianism, then, is that it appeals to thinkers across the political, moral and religious spectrum. And one of the most appealing aspects of Greed is Dead, at least for Salisbury Democracy Alliance, is that their decentralizing communitarianism leads them to regard Citizens’ Assemblies as being an ‘interesting innovation in democratic practice’.

What needs to be stressed in all of this, however, is that communitarians are not advocating that the collective should crush the individual but, rather, that given sympathetic conditions the individual, properly understood, emerges out of the collective, is shaped by the latter but, in turn, given the opportunity, helps to shape the collective. As Collier and Kay write, it is through the collective that individuals find their fulfilment.