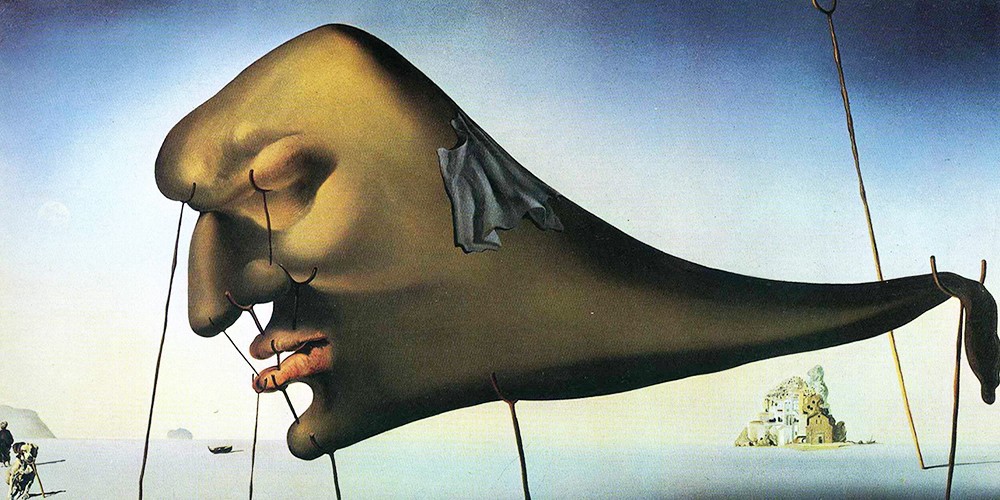

FOR some the Universe is simply absurd. This realisation happens when all our searches for meaning disappear into the silent Universe, which is indifferent to our petty struggles. It’s when we suddenly understand that we are not really attempting to save the planet against the ravages of climate change but just the flora and fauna (including humans) as they happen to be configured now – the planet will continue for the next 100 billion years or so before it is absorbed by the cooling sun.

But for philosopher Mariam Thalos this sense of absurdity happens when we step outside of the warmth of our collective lives into the cold of the ‘uncentred perspective’. And in an intriguing move in her book A Social Theory of Freedom she argues that this ‘stepping-out experience’ should actually ‘de-absurdize the life’ one lives because ‘afterwards it should feel warmer to reenter your life’. She adds: “If you feel a de-naturing of the world, upon stepping out of your life, you should feel a re-naturing of it upon your safe return.” Unfortunately for some of us this sense of de-naturing, absurdity and alienation persists if we ‘cannot execute the rentry’. Chillingly she writes: “They are those people who, prior to stepping out, lived without a sense of solidarity with others, for you will have an incentive to reenter and resume a much more enlivened life for the sake of those who mattered before you executed your initial exit.”

It may come as something of a surprise to learn that all this talk about solidarity comes at the end of a book about human freedom. But it is essential to her case because for there to be freedom at all there has to be a Self and it is this initial separation that creates that Self in separation from others. For her, and unlike Mary Midgley (who featured in Escaping the cage of the Self on this blog), the Self emerges out of the collective and we humans are ‘shifting constantly back and forth’ between the two – always supposing one isn’t stuck out in the cold of course.

Thalos describes herself as a compatibilist, which normally means that you accept the terms of determinism but believe that human freewill is compatible with it – indeed many argue that determinism is essential for freewill. They deploy what is called interventionism, which means that although we are subject to the laws of nature, we are able to intervene and effect our own free actions. Thalos, however, argues for a form of compatibilism but one whose ‘conception of freedom will skirt the problem of determinism’. Instead, Thalos argues that freewill is centred on the Self, embedded in solidarity with Others. But crucially the Self cannot be found in experience – as Gilbert Ryle memorably discovered in The Concept of Mind – because it isn’t there. For her freedom is a logic and, she insists, logic is not subject to the laws of nature. From an existential perspective, she argues that the Self is a concept – more precisely a self-conception that emerges out of the logical ‘fit’ between an agent’s conception of themselves and the facts of their circumstances. It is in this very struggle between her self-conception and the constraints she encounters in society that her freedom emerges. Thalos insists that this concept of freedom is a logical, not empirical, form, even though it seems at times as though she is carrying out a delicate high wire act that is in danger of collapsing into the empirical and, presumably therefore, deterministic world.

Ryle is famously takes a derogatory line against Descartes’s ‘I’ which he brands the ‘ghost in the machine.

But Thalos is much more sympathetic to Descartes. “Bodies, as Descartes envisioned, are under the sovereignty of the laws of motion (that we might refer to today as causal laws or dynamical laws), but minds are not. Mind is in no way a space-filler, subject to the laws of motion. Mind is subject to the laws of thought, to laws of reason, hence the separation between mind and body,” she writes.

Where Descartes went wrong was to jump to the conclusion that the ‘I’ was out there in experience. What in fact he had stumbled upon, according to Thalos, was the ‘logic of experience’. And even if, like David Hume and Ryle, we can find no evidence of the Self in experience, it does not follow that we should dispense with the Self. The logic of experience is ‘a theory of action that speaks of ongoing activity mediated by a Self (constituted in part by a self-conception) that is in turn subject to modification by a variety of interactions between Self and Others’.

One of the problems with this position is that it is difficult to see how the purely logical form of the self-conception can interact with Others without collapsing into the empirical world of causation. It is also in danger of a horrible circularity in that saying that the Self is a self-conception is close to the trivial statement that the Self is the Self. And it sails perilously close to the infinite regress because if we say that the Self creates the Self, who creates the original Self?

Although she doesn’t refer to it herself, the solution to the last two problems may be provided by the multi-disciplinary work of Kristina Masholt in Thinking about Oneself in which the author concludes that the Self proper is preceded by a non-reflective self which is able to develop a sense of the reflective Self through its entanglement with the Other. This idea seems to mitigate our concerns about infinite regress and circularity while establishing the foundations of a self which, on Thalos’s account, only achieves freedom when it steps out of the collective. But there remains two major problems: the first is the ever-present danger of collapsing into determinism and the other is that all this talk about the logic of the Self threatens to make freedom the preserve of the educated elite.

It’s fair to say that Thalos is sceptical about the truth of determinism but, nevertheless, is determined to escape its orbit. She attempts to achieve escape velocity by asserting that we do not ‘need to accept exclusively physicalistic, behaviouristic or biological terminology in the description of human behaviour. Instead, she argues for the social sciences because they are not universalistic like physics and biology but are ‘much more sensitive to the presence of individual variation’.

Her attempt to escape the elitist threat involves the use of what she calls Imitative Reasoning in which role models perform the function of creating the ‘fit’ between an individual’s conception of her self and her social circumstances from which her freedom emerges.

Thalos’s book has more surprises and plot twists than Line of Duty and as a result it is difficult to navigate one’s way through the thicket of ideas. It is not clear whether she has succeeded in freeing freedom from the clutches of determinism or whether her conclusion is as disappointing as that of the long-running TV show.